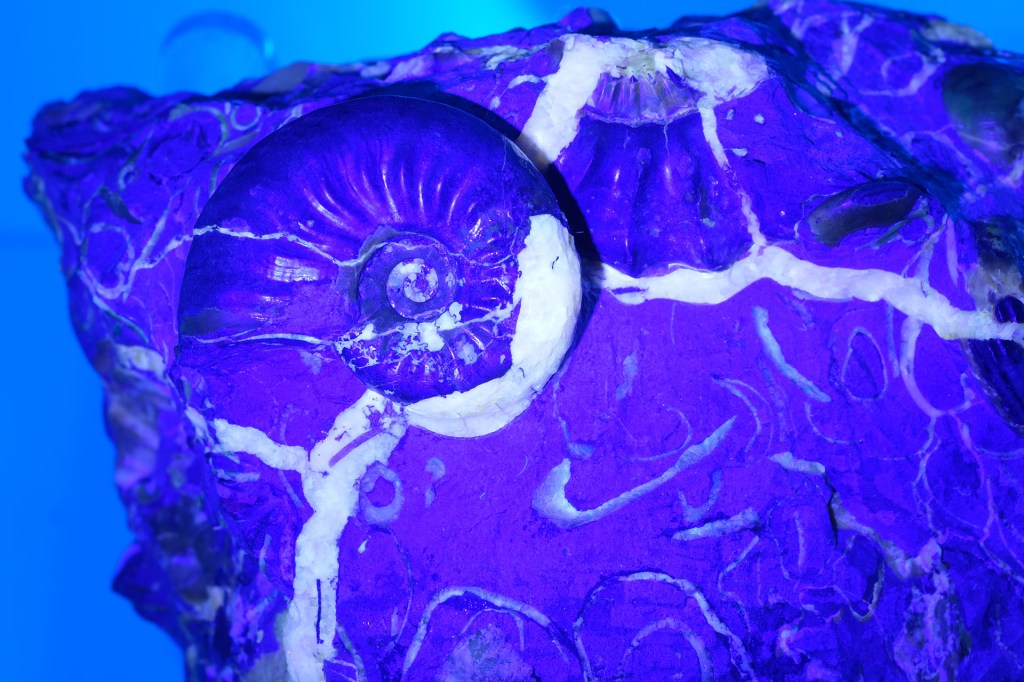

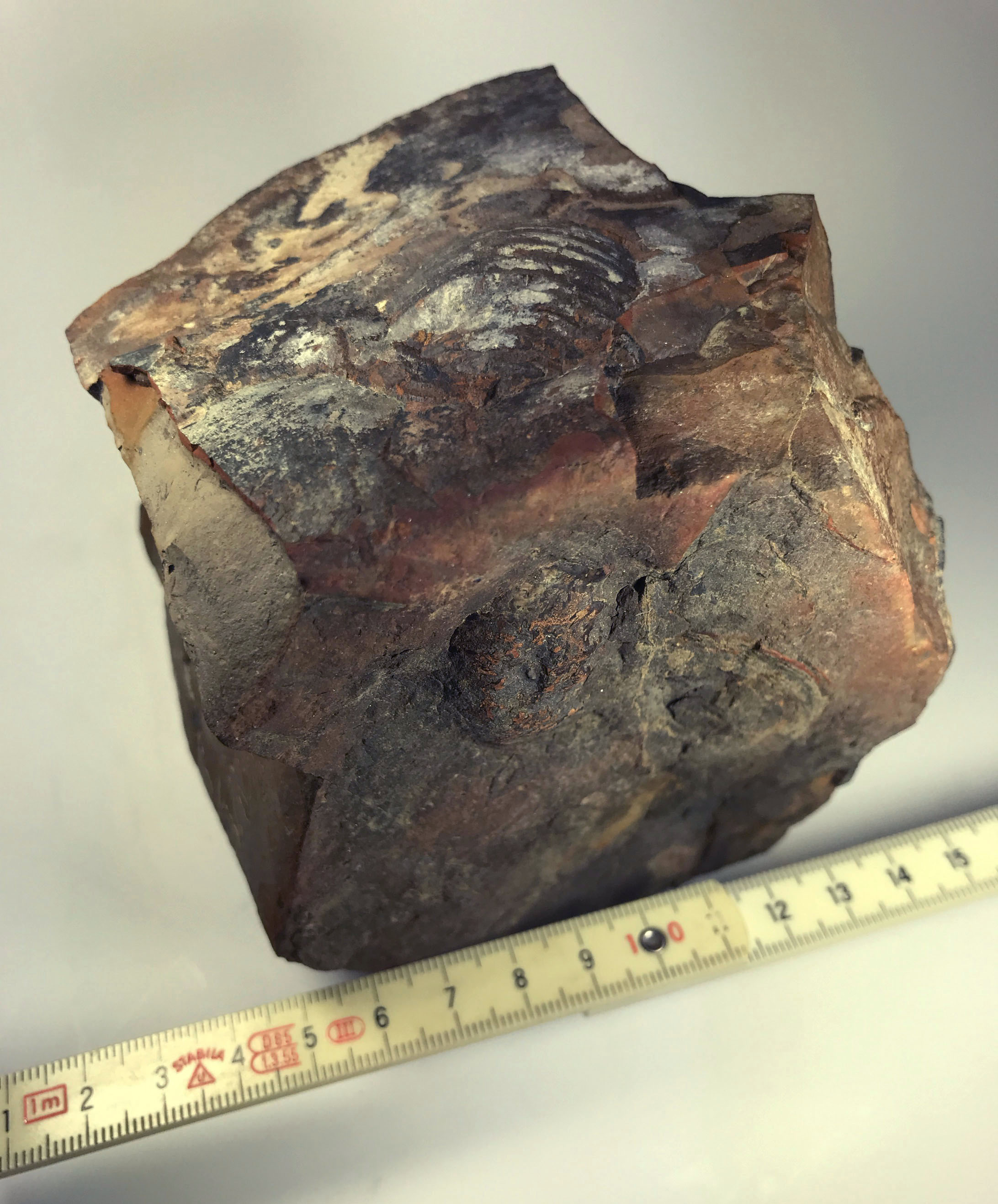

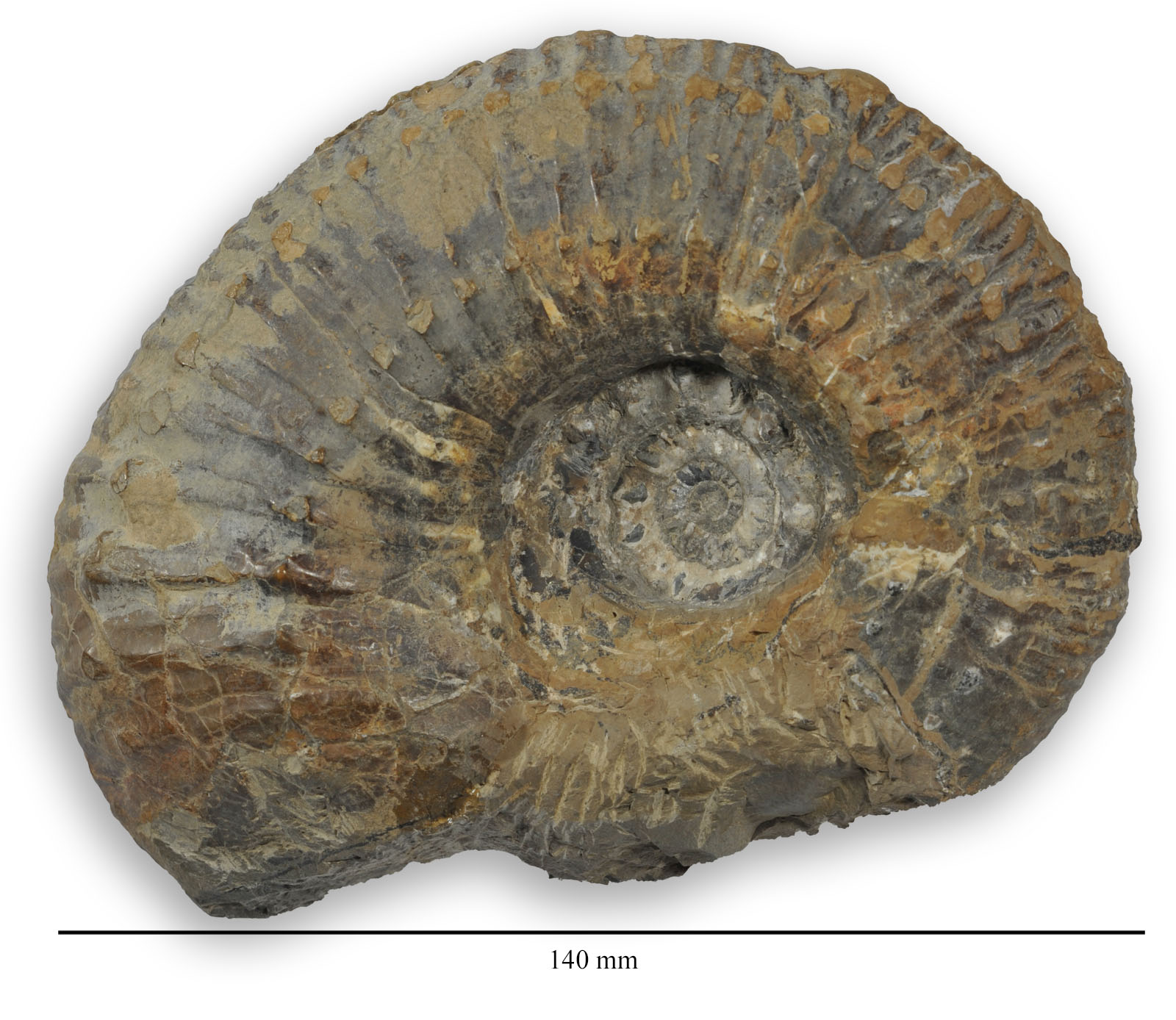

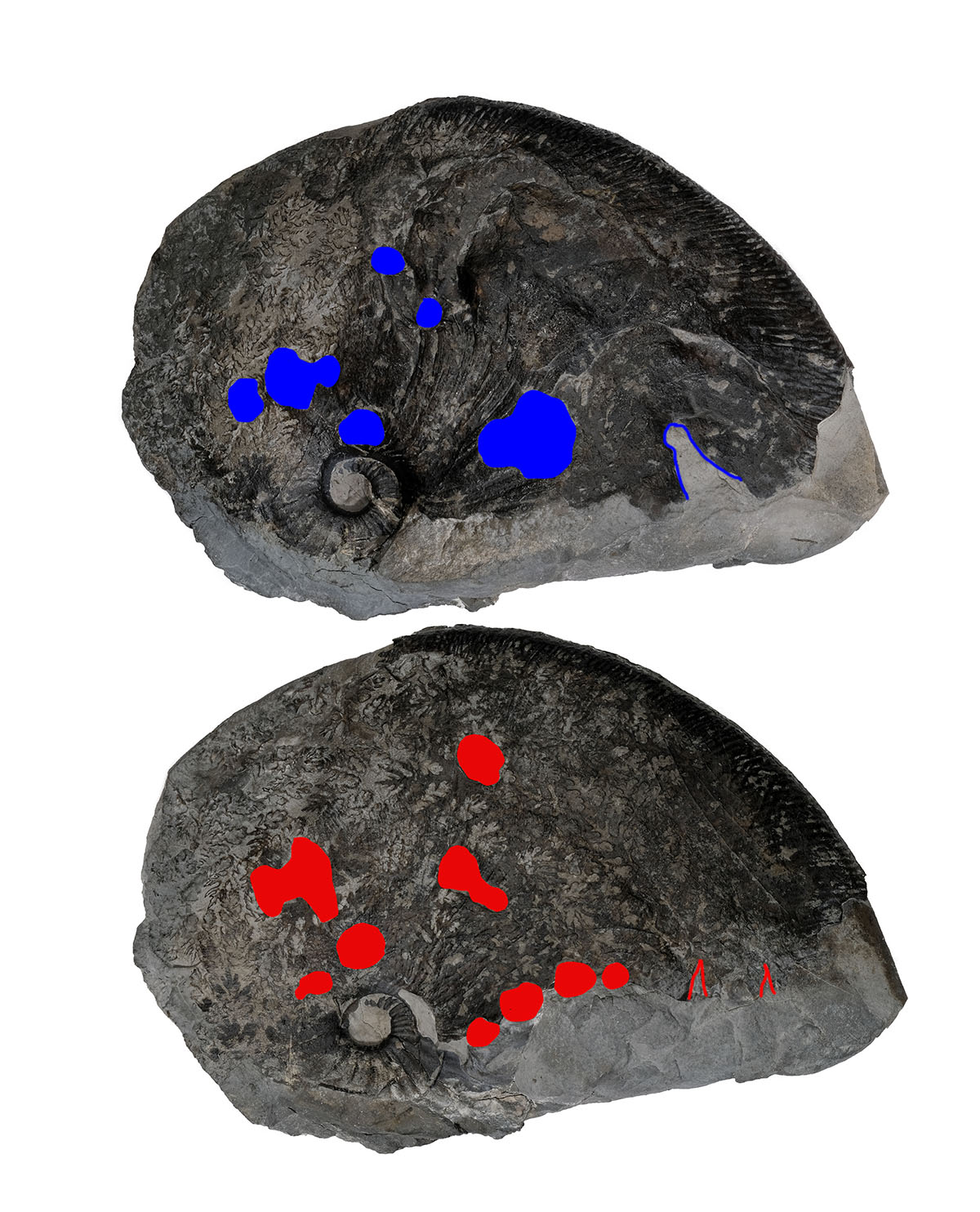

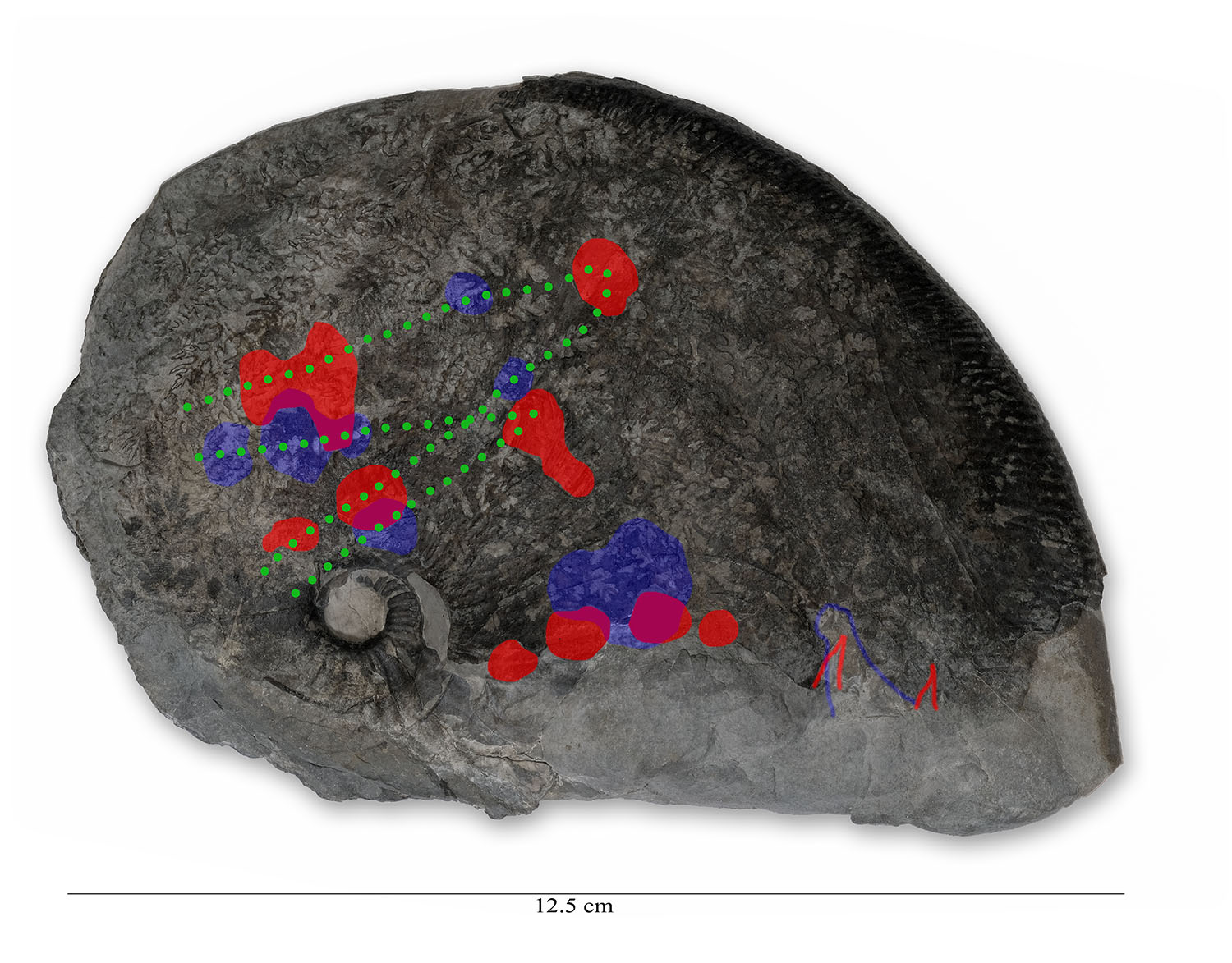

Nodicoeloceras incrassatum (4.5 cm) and Harpoceras falciferum (10 cm)

Purchased from Yorkshire Coast Fossils / Mike Marshall

This has taken a while. Nodicoeloceras has been a rare ammonite to find for me, mostly I guess since I tend not to collect a lot in places where the beds that Nodicoeloceras occurs in are the dominant ones.

If you look back to my link Catacoeloceras post from 2015 (how time flies…), you’ll be reminded that Nodicoeloceras occurs from exaratum to commune subzones.

Over the years I have therefore taken opportunities that presented themselves to buy Yorkshire coast Nodicoeloceras specimen – that’s why the photo texts read a little bit like the who-is-who of dealers of Yorkshire fossils .

Now Catacoeloceras and Nodicoeloceras can be very similar, so to be absolutely sure I preferred specimen that were accompanied by a characteristic subzone ammonites, e.g. Harpoceras (like the above gorgeous Harpoceras falciferum from Mike Marshall’s Yorkshire Coast Fossils).

Nevertheless, Nodicoeloceras still proved to be quite mysterious to me, defying deeper understanding.

This is also why I chose to make this post a “first” in so far as it is a guest post / dialogue with my good friend Neil Trudgill.

Neil has made great advances in identifying ammonites by their suture. If you have any experience collecting ammonites in the Yorkshire Toarcian, you will know that a suture on a toarcian Yorkshire coast ammonite is rather more an exception than the rule due to preservation.

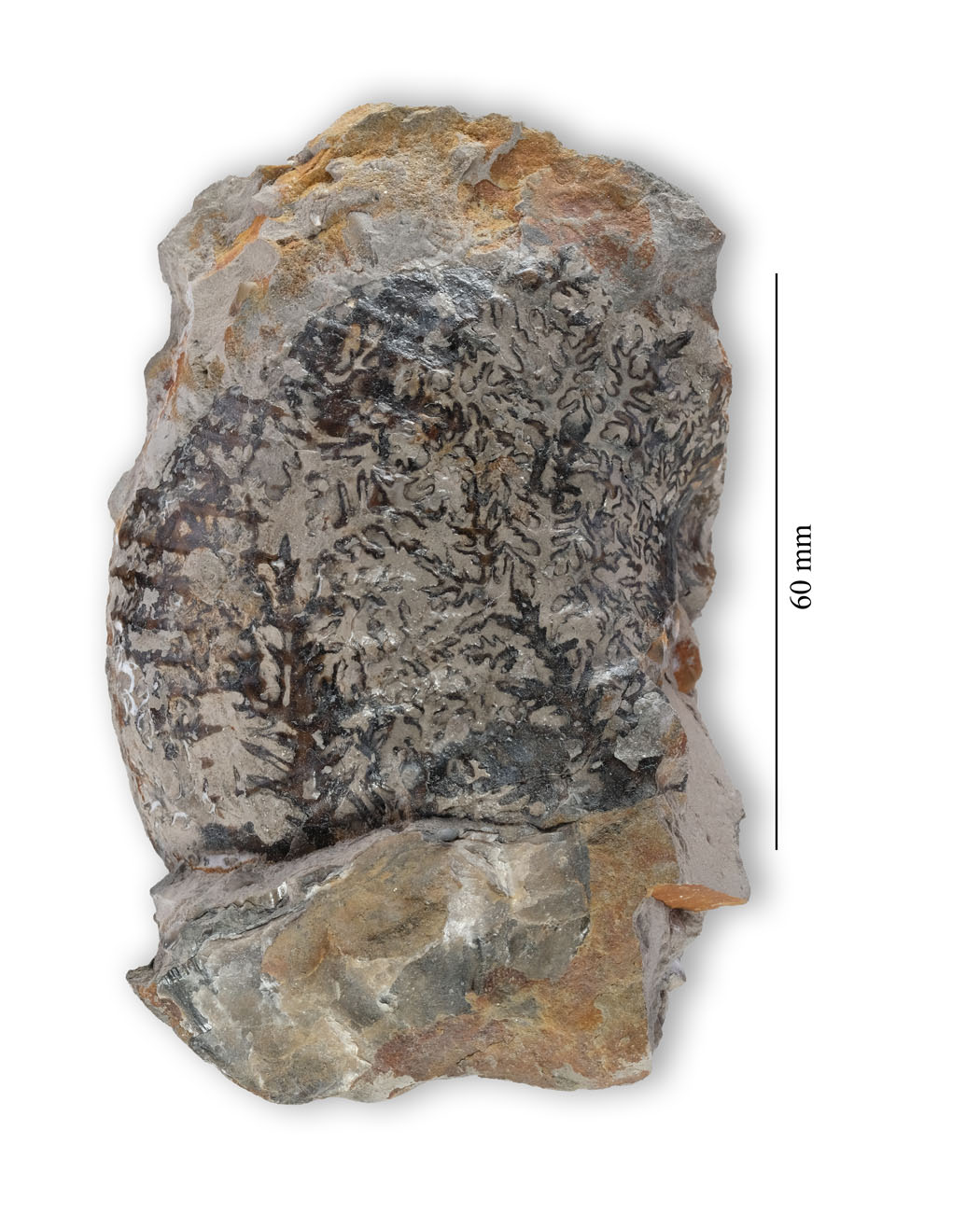

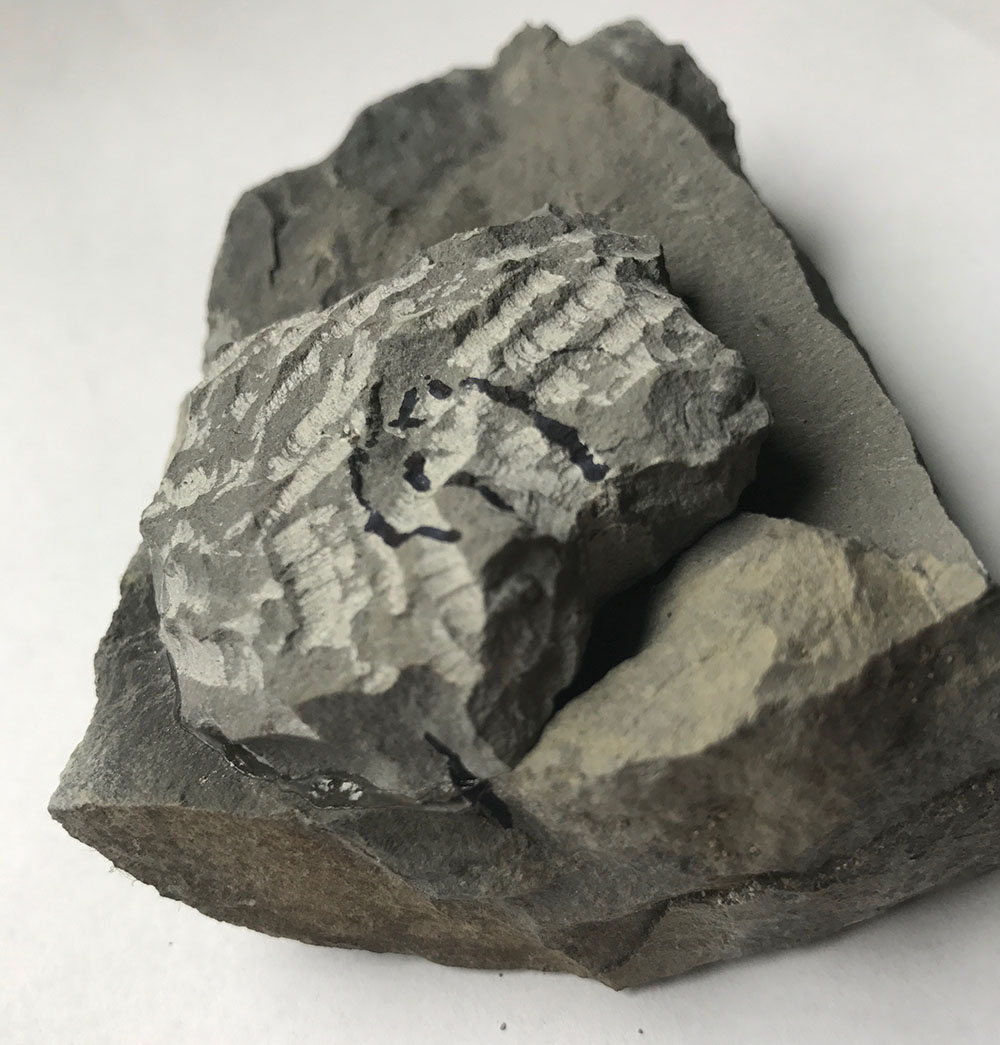

Nodicoeloceras incrassatum (7 cm)

Seavington St Mary/Somerset.

Purchase from FossilsDirect

Selected for the perfectly visible suture…

That’s where one of Neil’s most impressive “hacks” comes into play: He took every digital picture of ammonites he could get his hands on, especially holotypes, checked them for sutures and re-traced their sutures on top of the ammonite pictures, thus making the sutures available as an identifying characteristic (alongside other morphological features and stratigraphic indicators where available). This is how the identifications of the Nodicoeloceras in this blog were done. Neil has taken it much further than that, and will in due course create his own publication about the evolution of Dactylioceratidae and other families of Yorkshire ammonites – expect to see great things from him in the near future!

But enough of the introduction, pictures are from ammonites in my collection, identifications & further text by Neil – enjoy !

Nodicoeloceras – parallel evolution or a question over genus?

The genus Nodicoeloceras (Buckman 1926) is part of the Dactylioceratidae family, which dominated much of the Toarcian (Upper Lias), and which includes other genus of this period such as Dactylioceras, Peronoceras, Zugodactylites, Porpoceras, and Catacoeloceras.

Nodicoeloceras are found in the Lower to Middle Toarcian (Serpentinum Zone to Bifrons Zone), first occurring in the Exaratum Subzone (Serpentinum Zone) and extending probably throughout the Commune Subzone (Bifrons Zones).

They can be easily confused with species of the genus Catacoeloceras which is found later in the Crassum Subzone of the Bifrons Zone and in the lowest part of the Variabilis Zone.

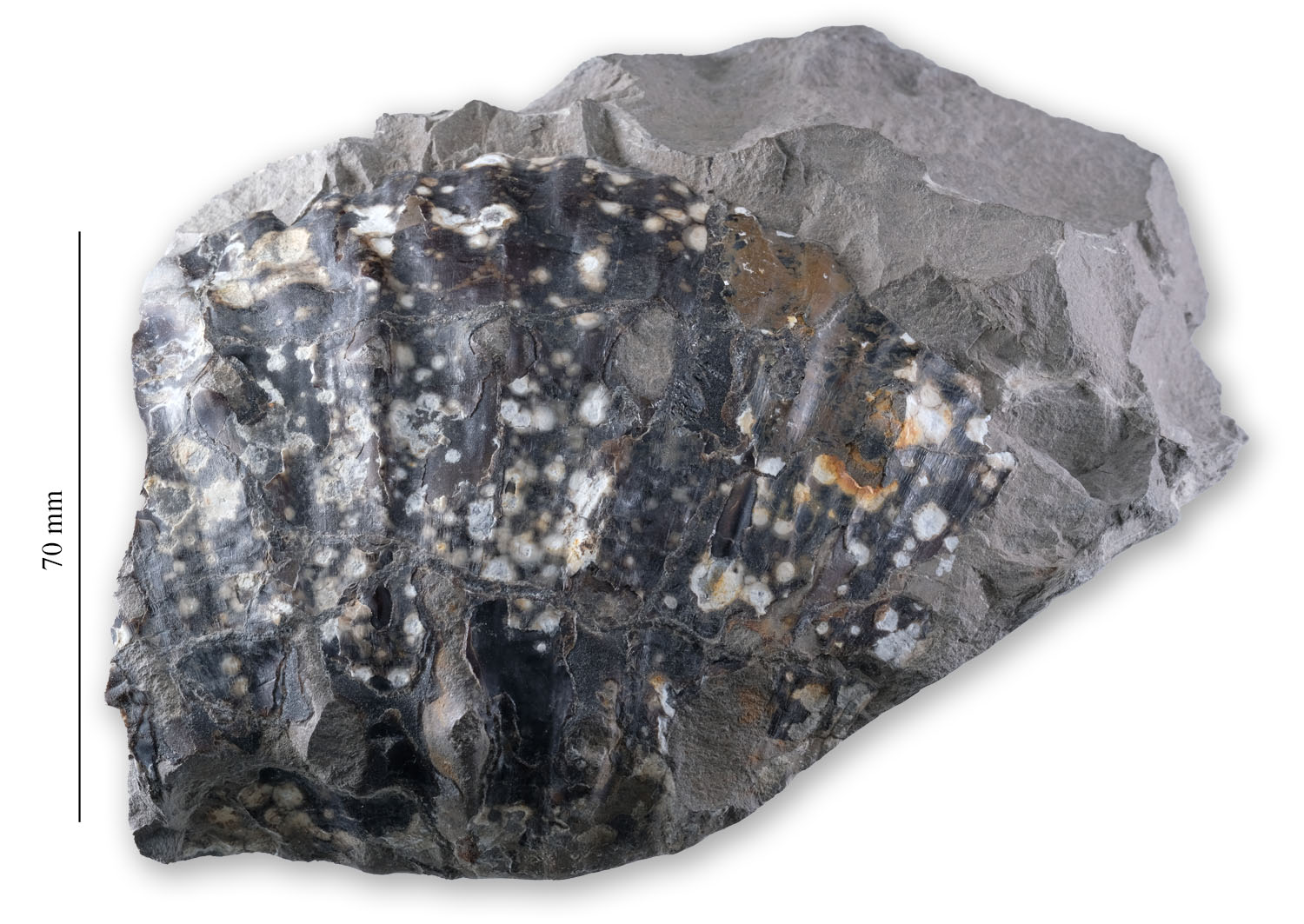

Nodicoeloceras are often described as relatively broad and moderately evolute, usually with depressed cadicone inner whorls (rounded subtrapazoidal section with notably inward sloping flanks and well-defined ventral-lateral shoulder) that usually have small tubercles / spices, with a subquadratic to subrotund outer whorl (body chamber) than usually lacks spines.

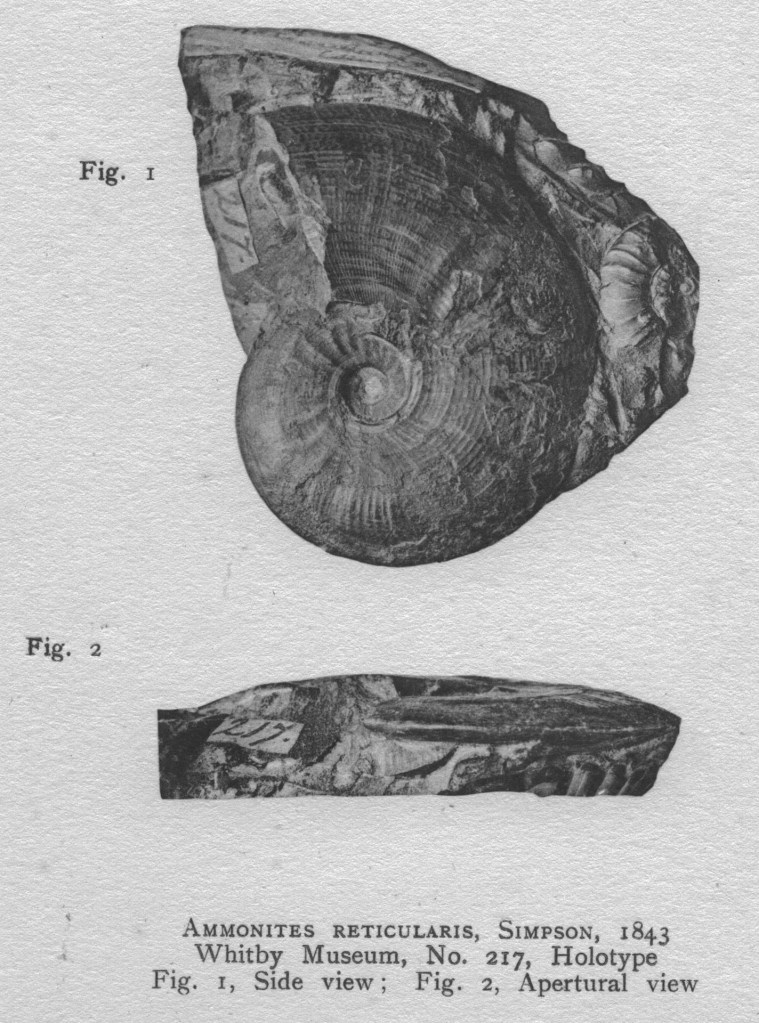

However, in truth they are often highly variable, including at species level, with the type species Nodicoeloceras crassoides (Simpson 1855) being the prime example.

Interestingly in Yorkshire there appears to be two different evolutionary lines to this genus (with one much rarer than the other), although this is not actually that unusual. For example, there appears to be two such parallel lines for Dactylioceras in both the Serpentinum and Bifrons Zone (but that’s for another time).

The thing that is of note that the two parallel Nodicoeloceras lines have quite different suture patterns, with one evolutionary pathway having a notably simpler suture line than the other.

Certainly, both part of the Dactylioceratidae family and Dactylioceratinae subfamily, but if truly part of the same genus? A question to which I find myself pondering whilst writing this, but certainly with no clear answer.

Nodicoeloceras crassoides (Simpson 1855) Line 1

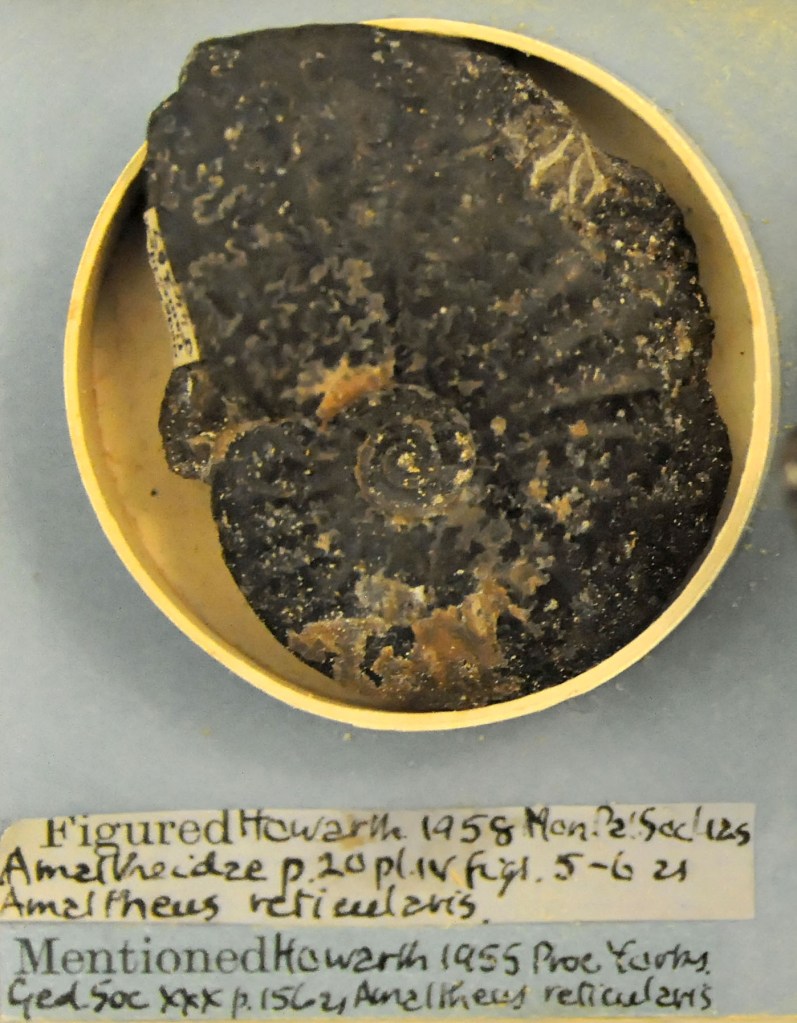

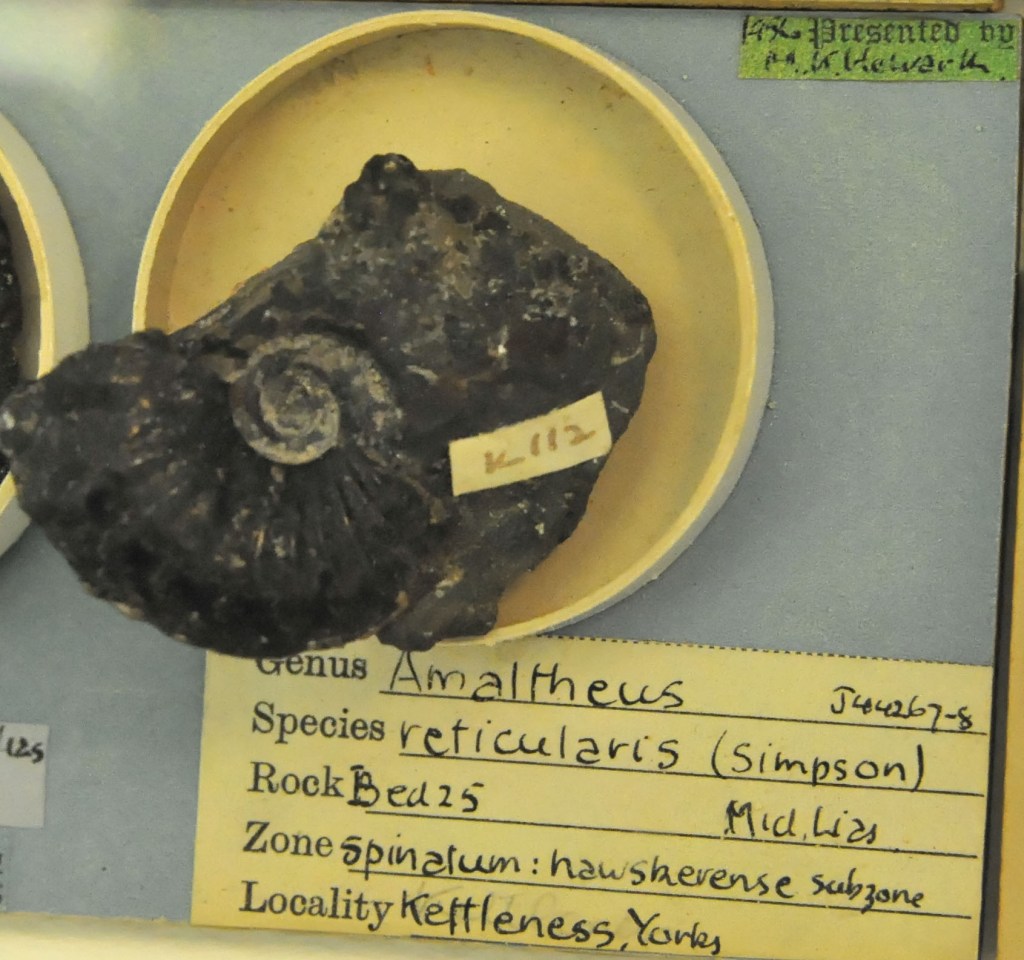

Nodicoeloceras crassoides (5 cm) Yorkshire coast, purchased from Stone Treasures/Mark Hawkes

Nodicoeloceras crassoides (6.5 cm) Yorkshire coast, purchased from Fossils-UK / Byron Blessed

Nodicoeloceras crassoides (6.5 cm) Hawsker Bottoms. A very lucky split. Matrix obviously falciferum zone, this had me confused for a long time due to its fibulation and nodes.

Highly variable species, especially with regards thickness (usually whorl thicker than high, but sometimes closer to equal), whorl section (which can be anything from round to subtrapezoidal) and tubercles (usually in form of small spines of inner whorls but can vary in size and can occasionally form on the body chamber). Inner whorls frequently depressed and may be cadicone / coronate, but these are certainly not defining features as often referenced and are highly variable. Fibulation can also occasionally occur. Can be found within the so-called pyrite skinned ‘Curling Stones’ of bed 37 of the Exaratum Subzone (Serpentinum Zone). Simpson’s Nodicoeloceras fonticulus appears to be coronate inner whorls of thicker form, and therefore a synonym (as previously proposed by Howarth, and I suspect from my observations that Dactylioceras crassifactum (also Simpson) is also a synonym.

Nodicoeloceras incrassatum (Simpson 1855) Line 1

Nodicoeloceras incrassatum (4.5 cm) From the prep backlog of the late Jeff Mulroy, prepped by myself.

Although probably not as variable as N. crassoides (from which it clearly evolved), it is still a variable species. This is especially true in terms of thickness and whorls section (variability of these similar to N. crassoides, with depressed but also non-depressed forms). Tubercles (spines) seem to be always small and restricted to the inner whorls, and I have not seen any examples with fibulation. Both depressed and non-depressed forms seem to be relatively common (it is notably the most common of Yorkshire’s Nodicoeloceras species). Often found in association with Harpoceras falciferum and Dactylioceras gracile (true specimens of which appear to be likely microconch to N. incrassatum) most frequently in the Falciferum subzone of the Serpentinum zone. It can also be found in the lowest bed(s) (bed 49) of the Commune subzone of the Bifrons zone. From my observations I believe Simpson’s Dactylioceras crassulum is probably the same species and therefore a synonym.

Nodicoeloceras crassescens (Simpson 1855) Line 1

Dactylioceras athleticum (5 cm) and Nodicoeloceras crassescens (5 cm). This combo makes it likely that it came from bed 55 of the Alum shales. Purchased from Stone Treasures / Mark Hawkes

I suspect this species of the Commune subzone (lower and middle beds, but likely extending to the top) with its cadicone inner whorls armed with small tubercles (spines) belongs in the Nodicoeloceras genus. I believe it is also the likely descendant of Nodicoeloceras incrassatum. It shares morphological similarities to Catacoeloceras raquinianum (although crassescens may occasionally show fibulation) and can be hard to differentiate unless approximate horizon (beds) known (or suture visible).

Dactylioceras (Nodicoeloceras?) crassiusculum (Simpson 1855) is to my knowledge only known from the small ~3cm diameter (inner whorls) holotype and a single small specimen collected by Howarth from Ravenscar. Although I have a morphologically similar example, I do have some doubt over its validity as species and suspect the holotype could potentially be the inner cadicone whorls of Dactylioceras crassescens, especially as they seem to be from equivalent beds.

Nodicoeloceras crassescens is also a possible ancestor to Zugodactylites.

Nodicoeloceras spicatum (Buckman 1921) Line 2

Nodicoeloceras spicatum (3.5 cm)

Purchased from Stone Treasures / MarkHawkes

This very rare species is most recognizable by the small but distinct spines on inner whorls that usually initially regularly but then becoming more sporadic creating the distinctive inner whorls of this species. Fibulation (to varying degree) is also relatively common on inner whorls. It is found in the Falciferum Subzone of the Serpentinum Zone, but in Yorkshire as of yet I’m aware of only a single specimen from Holderness, whose preservation and matrix clearly indicates it’s derived from North Yorkshire. Perhaps a rare migrant to the basin, having its evolutionary roots elsewhere.

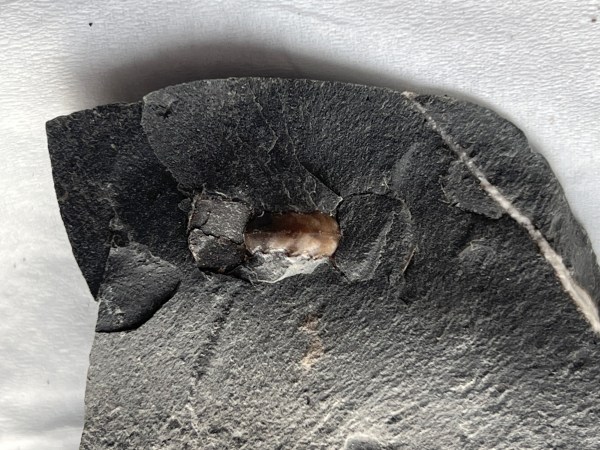

Nodicoeloceras lobatum (Buckman 1927) Line 2

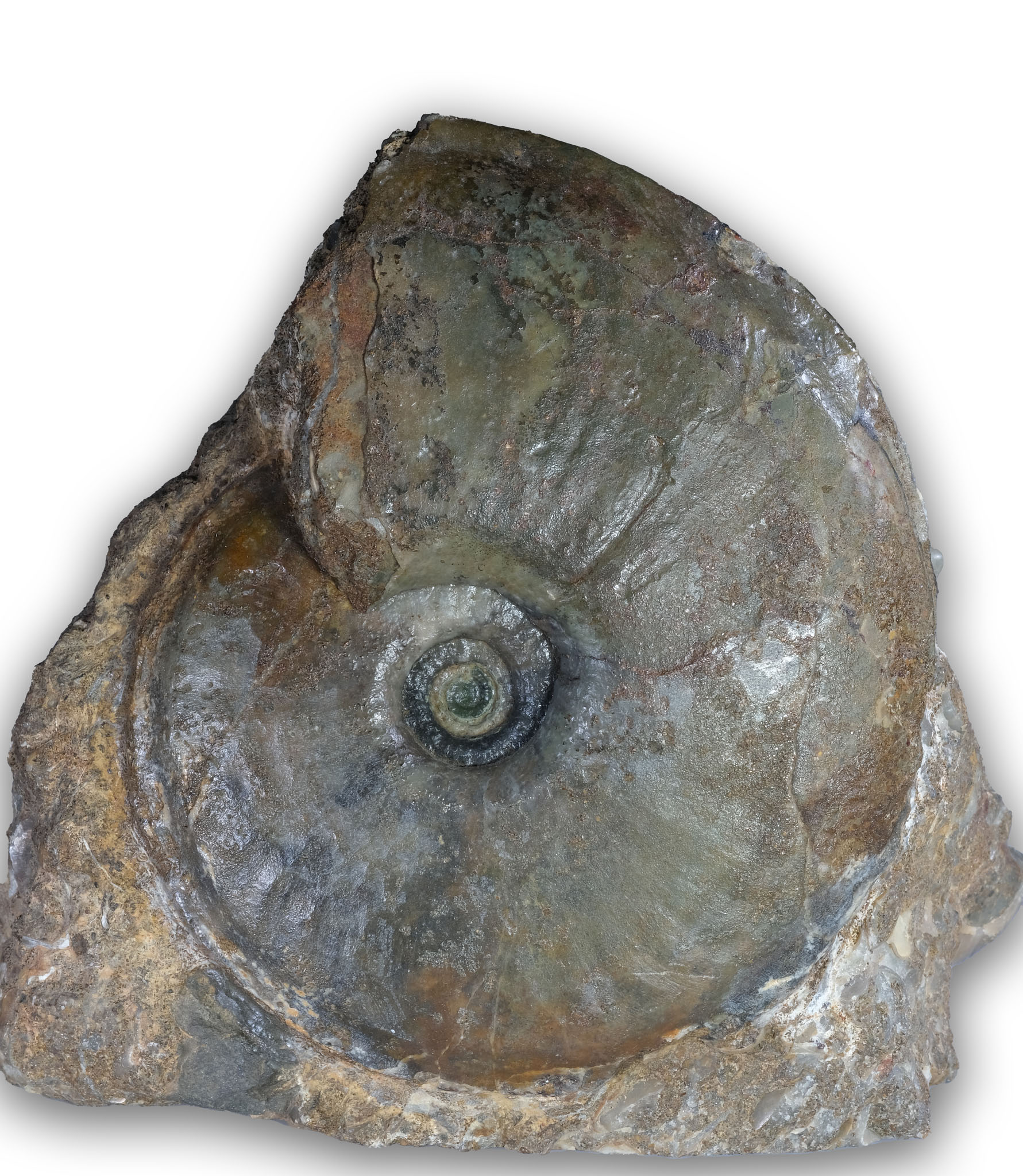

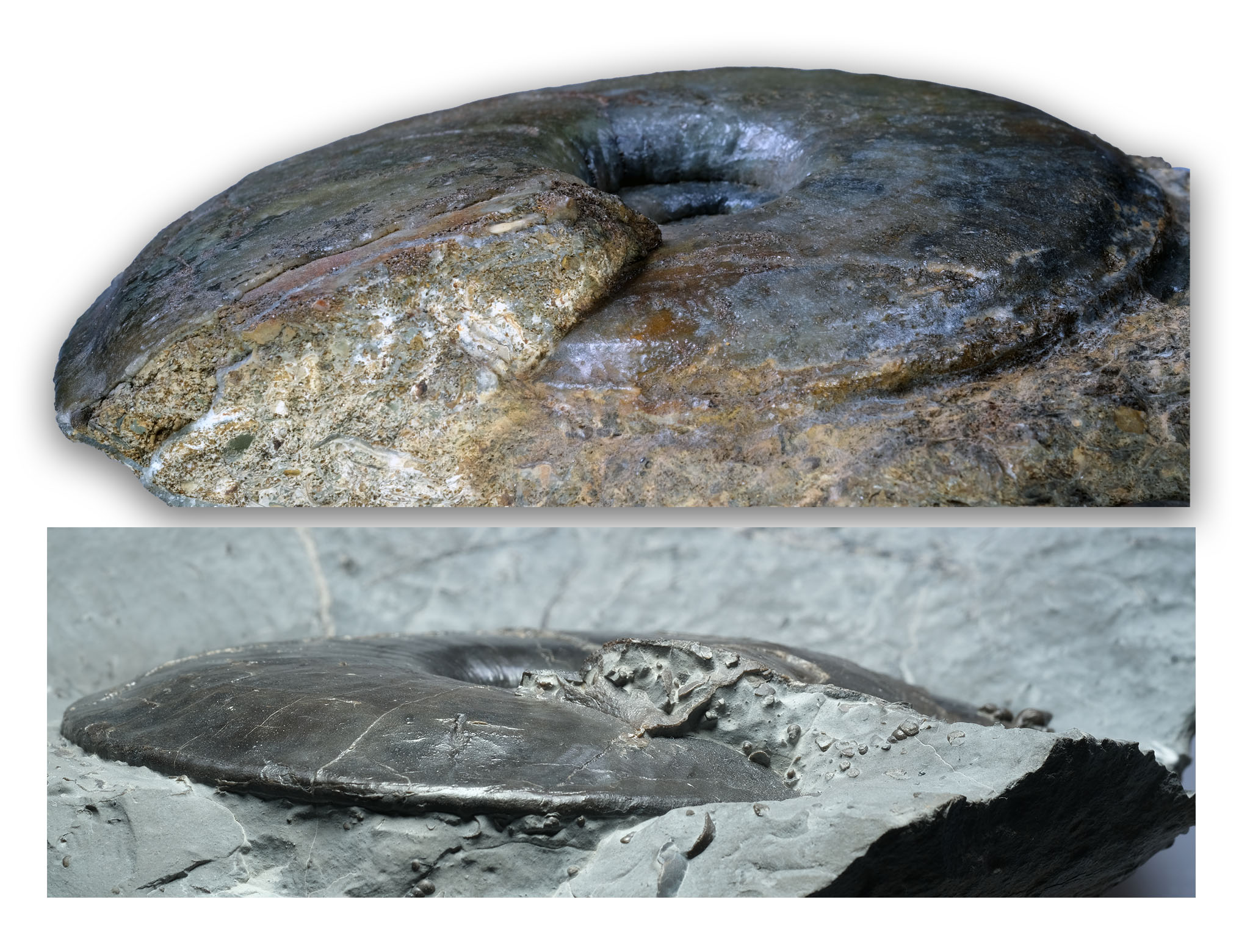

Nodicoeloceras lobatum (7.5 cm)

Port Mulgrave.

Must have been part of a septarian nodule, as showing significant calcite growth between shell and inner mould.

Purchased from Stone Treasures / Mark Hawkes

This rare species is found in the very upper beds of the Falciferum subzone, but seemingly more commonly (although still very rare!) in the lower beds of the Commune subzone. There appears to be less variability with a broad gently rounded ‘subrectangular’ whorl section with very small fine spines on the inner whorls. The suture suggests evolution from Nodicoeloceras spicatum is likely.

Nodicoeloceras multum (Buckman 1928) is very similar but generally with more depressed (usually cadicone) inner whorls. It is from the Bifrons zone, specifically the Commune subzone, and is likely the descendant of Nodicoeloceras lobatum. I haven’t verified it from Yorkshire yet, but this may be both due to rarity and lack of identifiable suture. There also appears to be a gradual transition from N.lobatum, which can make separation tricky. It is also similar to Dactylioceras crassescens, but with notably different suture.

Nodicoeloceras dayi (Reynes 1868) Line 2

Nodicoeloceras cf.dayi (7 cm)

Runswick Bay

From the collection of the late Jeff Mulroy,

purchased through Fossils-UK / Byron Blessed.

This very rare and usually very broad Nodicoeloceras with typical cadicone inner whorls (with spines) and usually distinct ventrolateral shoulder is said to be from the upper beds of the Commune subzone and potentially extending into the lower Fibulatum subzone. Suture suggests it evolved from Nodicoeloceras spicatum ancestry with Nodicoeloceras lobatum and Nodicoelioceras multum as likely predecessors. I have only seen a single likely specimen from the Holderness, although probably derived from North Yorkshire, and this pictures specimen in the collection of Andreas from the North Yorkshire coast.

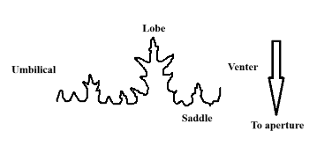

A NOTE

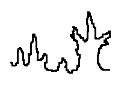

Please note sutures are drawn in this orientation:

Sutures have been drawn tp be „representative“ showing the main key features that might be observed in relatively well preserved Yorkshire specimens of such size range but it should be noted they may not include all the minute detail. They are more a ‘good’ general guide.