Pleuroceras paucicostatum, 90 mm, Hawsker Bottoms

The Yorkshire ammonites of the genus Pleuroceras have for some reason given me more

of a headache than other genera (not as much as the Aegoceras/Androgynoceras though !),

over the years I’ve made multiple attempts to get my head around the differences between

the species, but only the most recent and most thorough attempt has resulted in an

understanding satisfactory to me. At first glance, the species seem to be very similar, and

only when you dig deeper into morphological measurements such as rib count, relative

whorl height/breadth and most importantly, their stratigraphical position and appearance

of their surrounding matrix, their differences and development become clear.

As M.K. Howarth noted in his 1958 monograph about the Amaltheidae, some of the

species appear to have evolved in Yorkshire and therefore, transitional specimen are

common, which adds to the difficulty distinguishing some of them.

The following species occur in Yorkshire :

- P. solare

- P. solare var. solitarium

- P. apyrenum

- P. hawskerense transient elaboratum

- P. hawskerense

- P. paucicostatum

- P. birdi

For completeness, I’ve added one more species, which does occur in Britain,

though due to a non-sequence in the relevant beds, not in Yorkshire :

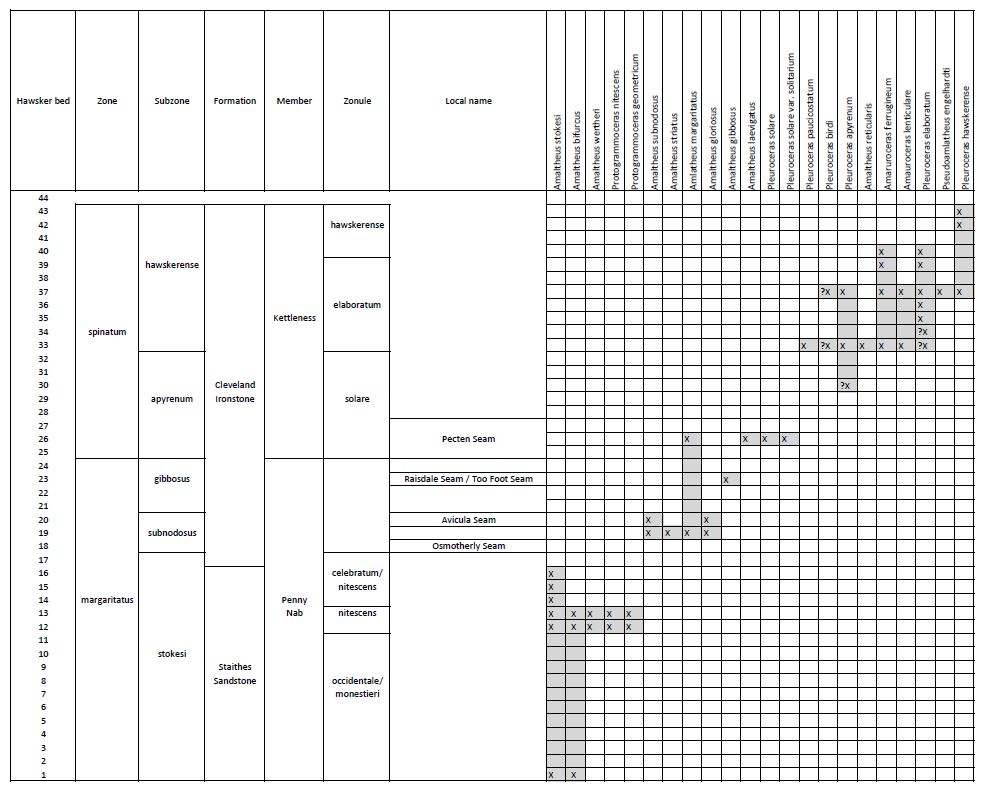

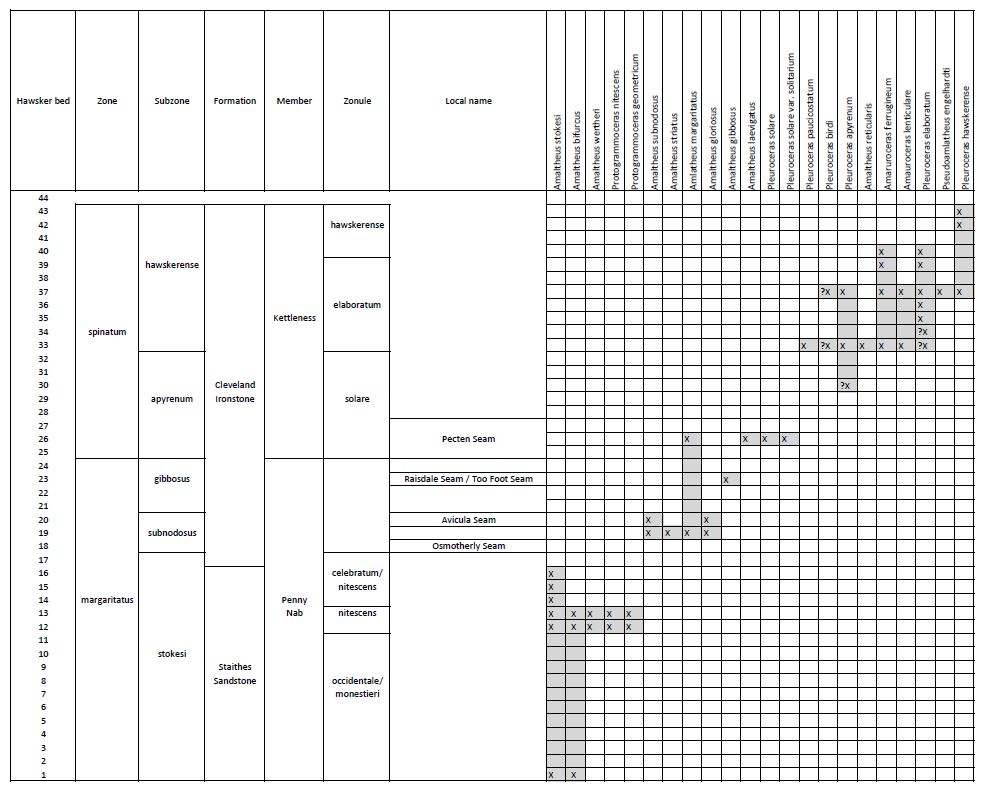

There potentially is a small overlap between genera Amaltheus and Pleuroceras,

but again it is relatively unlikely to find those genera together due to a non- sequence,

i.e. missing beds in Yorkshire – find a list of all Amaltheus and Pleuroceras species and

the bed numbers for Hawsker Bottoms (compiled from Howarth 1958, Page 2004)

below :

Occurrence of Amaltheidae in Yorkshire

This post also took longer to create due to the fact that I re-prepped a large portion of

the specimen, which predominantly have been found more than 10 years ago – that´s

not to say that chances to find specimen like these are lower today for most species,

though probably in no way as good as they were when M.K. Howarth wrote his

Amaltheidae monograph in 1958.

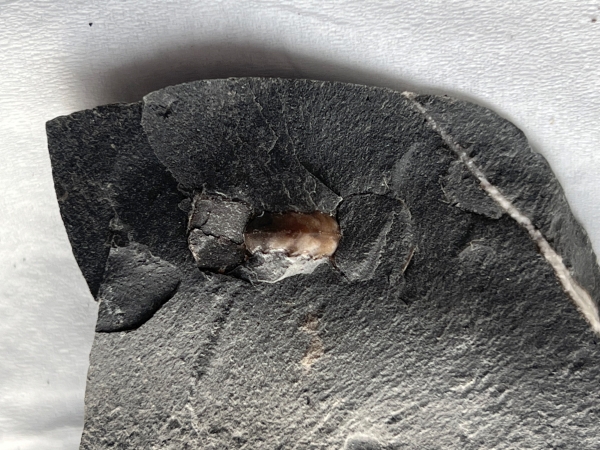

I had tried to air abrade a specimen that had a lot of fractured and torn light brown

shell and the result was so convincing (and addictive) that I did most of the specimen

in my collection. Here is an example of the transformation :

Pleuroceras paucicostatum, 60 mm, before and after air abrading with iron powder

But let´s get to the description of the different species, ordered more or less in ascending stratigraphical order.

Pleuroceras solare (PHILLIPS)

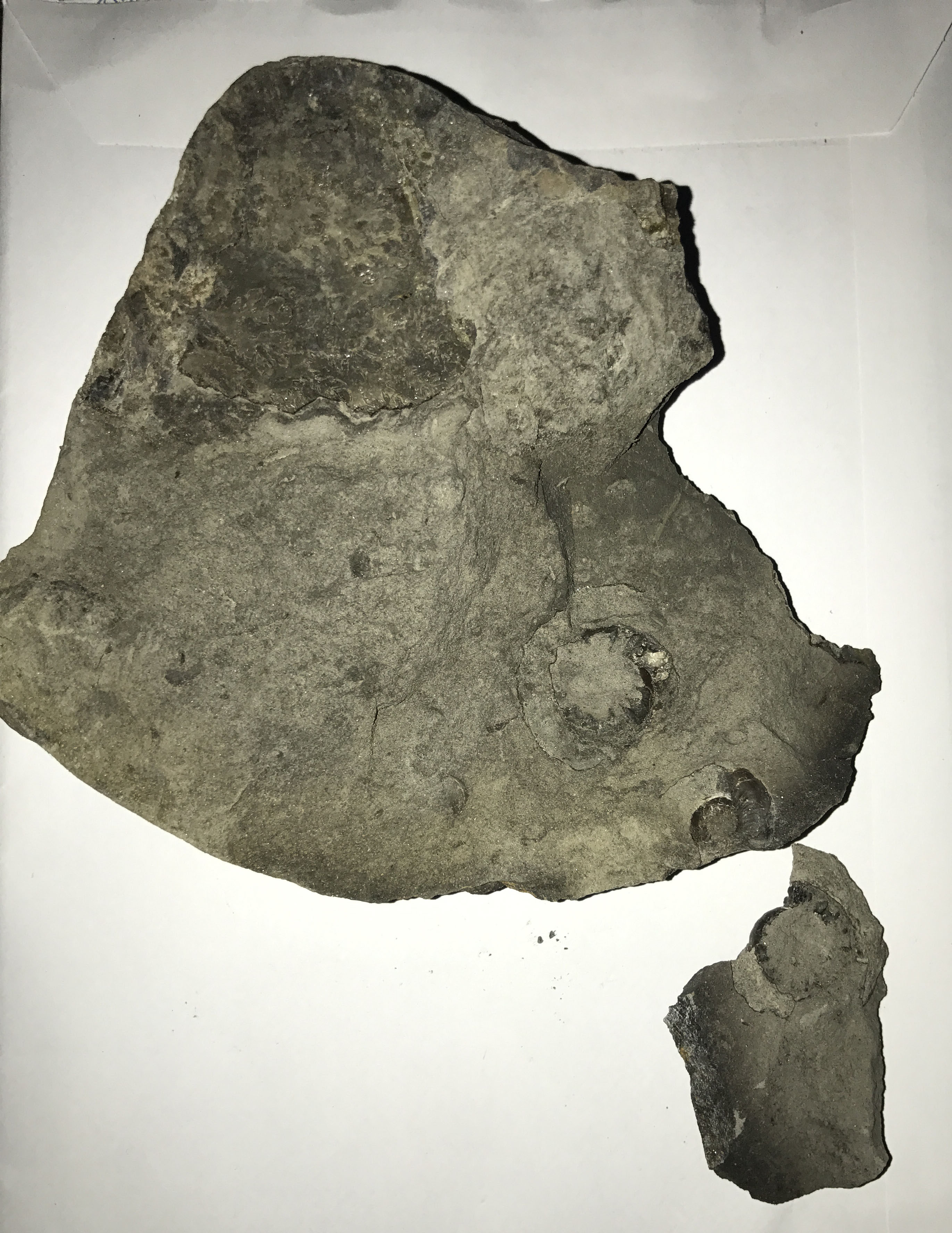

Pleuroceras solare, 80 mm, Hawsker Bottoms

Pleuroceras solare for me is a rare species – I´ve only got one in my collection,

and I´ve only realized I´ve had it during the research for this post.

It is significantly bigger than the neotype shown by Howarth, which added to

the difficulty in correctly assigning it. Preservation is markedly different from all

the other species, most significantly the matrix it is embedded in is oolitic,

typical for Hawsker bed 25, and the internal mould is preserved in

light brown / light grey calcite.

Pleuroceras solare, detail of ribs & keel

Ribs are sharp and swing forward at the edge of the venter, they do not meet the even

on the internal mould strongly crenulated keel, smooth areas at the side of the keel

remain. On the bigger outer whorls of this specimen the ends of ribs at the are slightly

heightened.

Rib density appears to be relatively constant, the cast of the neotype I´ve procured

from GeoEd (see also

here) has the same 28 ribs as myspecimen at almost double

the size.

Pleuroceras solare, 40 mm, cast of neotype, Hawsker Bottoms

Perceived rarity of these ammonites may also have something to do that Hawsker

bed 25, the “Pecten Seam” is only about 40 cm thick – my find did not come from

in situ, note to myself : Goal for 2016 = find bed 25 in situ…

Pleuroceras solare (PHILLIPS) var solitarium (SIMPSON)

Pleuroceras solare var. solitarium, 41 mm, Kalchreuth/Germany

This ammonite, though it should occur in Yorkshire, has not (yet) been found by me,

so I´ve procured a specimen from the german Kalchreuth quarry.

The only difference between this one and P. solare is that the var. solitarium has

larger tubercles on the inner whorls, and therefore a lower rib density up to 25 mm.

A specimen in the Whitby museum is displayed here :

http://www.whitbymuseum.org.uk/type/grp11/wm500.htm

Pleuroceras paucicostatum HOWARTH

Pleuroceras paucicostatum, 80 mm, with slight pathology, Hawsker Bottoms

P. paucicostatum has less dense ribs than P. hawskerense, especially visible on

the inner whorls. Ribs are straight and strong, there is a sharp bend forward

at the edge of the venter, the keel is strong and almost smooth on the internal

mould. Especially on the inner whorls the ribs are a little thicker and slightly

raised on both ends.

I my collection this appears to be the most common species, but I´m sure this

is due to severe collecting bias – once you know what nodules from Hawsker

bed 33 look like, and that they often contain ammonites, you´re more likely

to look for them again…

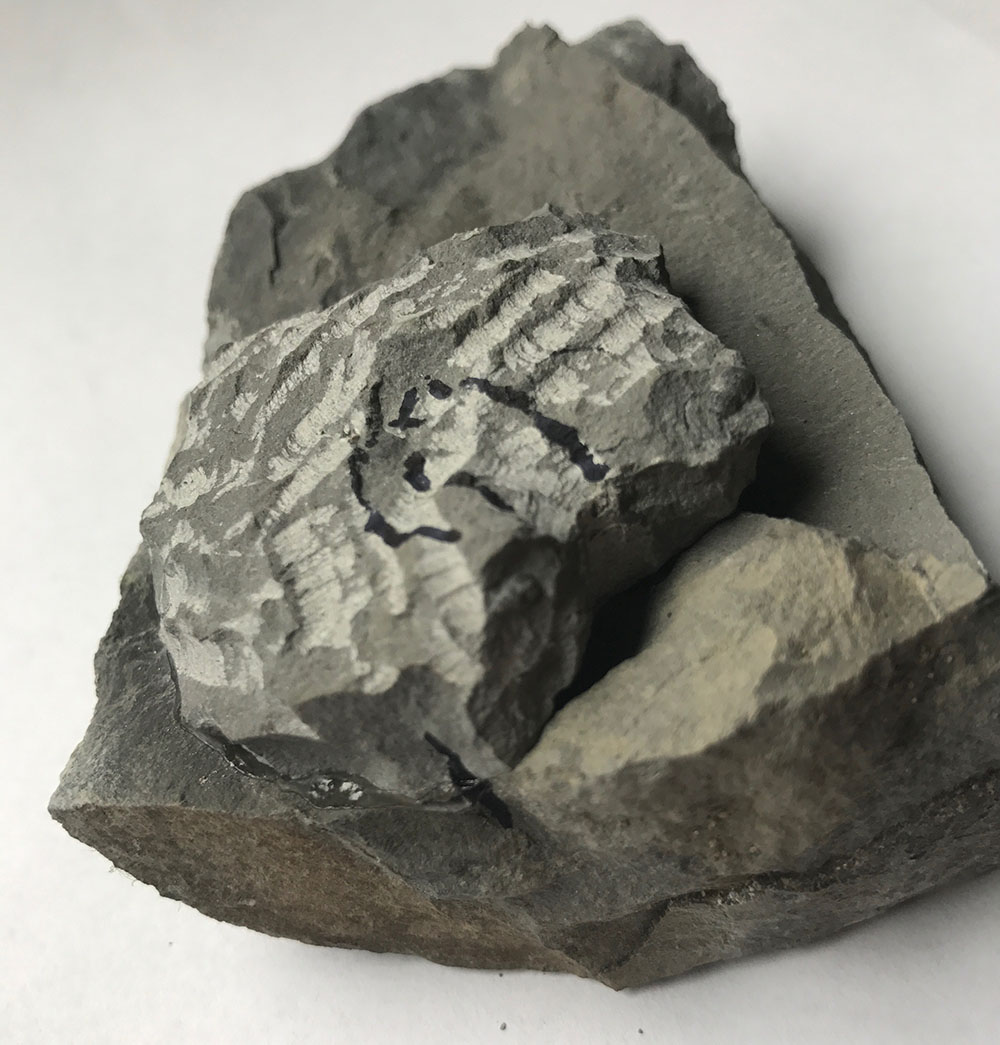

Detail of Pleuroceras paucicostatum, showing sutures and ribbing

Pleuroceras birdi (SIMPSON)

I have not yet found P. birdi, which is very similar to P. paucicostatum in everything

except whorl breadth – the whorls of P. birdi are significantly thicker.

Only 2 specimen were known at the time of writing of Howarth´s monograph,

one from Hawsker Bottoms, one from Raasay.

The holotype is in Whitby museum (WM278) and can be seen on their website at

I have to look at that specimen “live”, from the picture there appears to be a bit of a

bend at about 1 o´clock in the shell and a successive increase in whorl thickness –

a possible parasitic growth on the shell and potential cause of a forma aegra augata ?

The specimen seems to be preserved on one side only, the other side appears

to be eroded – if indeed the specimen is pathological, a possible structural

compensation cannot be estimated.

Pleuroceras salebrosum (HYATT)

Pleuroceras salebrosum, 60 mm, Holderness Coast (coll. A. Tenny)

Pleuroceras salebrosum is unlikely to occur in Yorkshire – both the transiens and

salebrosum zonules appear to be missing in the beds (PAGE 2004).

Nevertheless, a magnificent specimen has been found by A. Tenny

(superb prepwork by M. Marshall) on the Holderness coast – it´s pre ice age origin

is unclear.

Many thanks to Andy Tenny for letting me photograph this great specimen.

Pleuroceras apyrenum (BUCKMAN)

Pleuroceras apyrenum, 81 mm, cast of holotype

I´ve shown the GeoEd cast of the holotype before, the main reason to procure

this cast was of course to verify identification of my Hawsker specimen

of P. apyrenum. Over the 27 years of collecting on the Yorkshire coast,

not many specimen of P. apyrenum have found the way into my collection,

and it is the Pleuroceras species I´ve had the most trouble of getting it

identified to an acceptable degree of probability.

With P. apyrenum, there appear to be 2 variants; one where the ribs get reduced

to a fine striation from up to 30-40 mm, and another one where this does not

happen, like in the holotype. I have so far at Hawsker only found specimen up

to 60 mm and a large fragment, where no reduction of the ribs takes place,

and some smaller specimen with an early reduction of ribs.

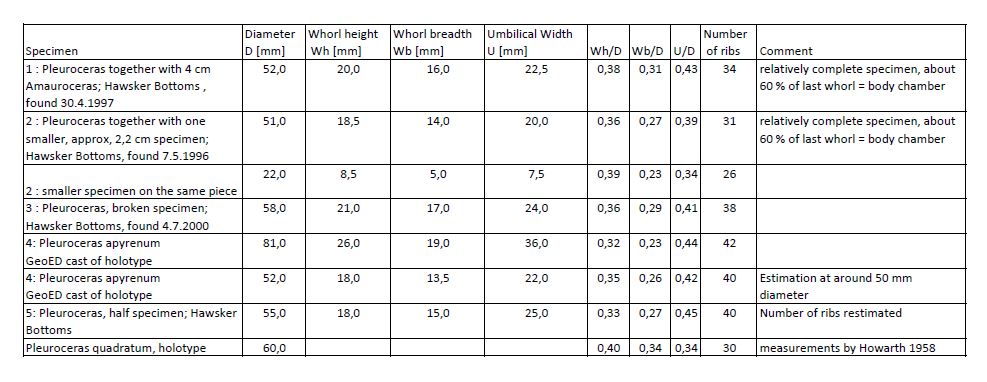

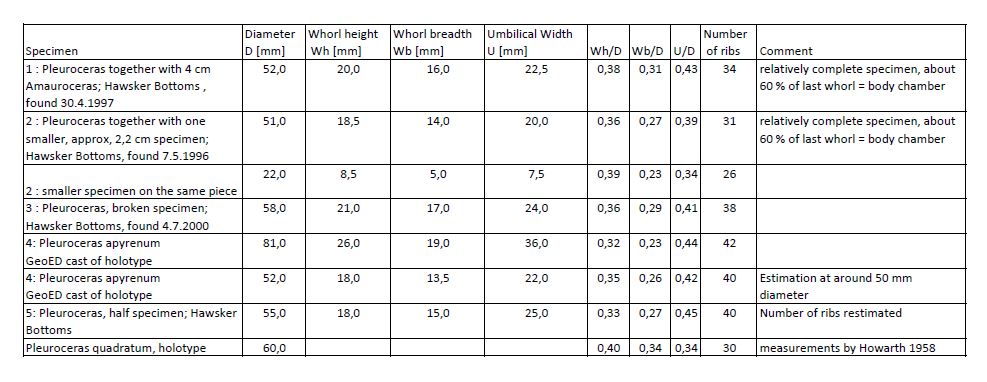

Measurements of P. apyrenum specimen

All specimen have been measured and fall into the variation breadth of P. apyrenum.

One specimen is somewhat closer to Pleuroceras quadratum, especially to the

specimen on table VIII, 4a,b which unfortunately has no measurements listed in

Howarth´s monograph and was not available as a cast.

Some of the specimen are also available on GB3D at http://www.3d-fossils.ac.uk/,

a great initiative making museum specimen available as high-resolution 2D and 3D

pictures.

At the moment I´m not totally convinced that P. quadratum is only occurring outside

of Yorkshire, or for that matter that some of the specimen listed in Howarth´s

monograph as P. quadratum should not really be P. apyrenum.

A note for my continental readers who wonder about what P. apyrenum looks like in the UK –

the continental “version” of the same age indeed looks slightly different,

and often develops tubercles which are unknown in the Yorkshire population.

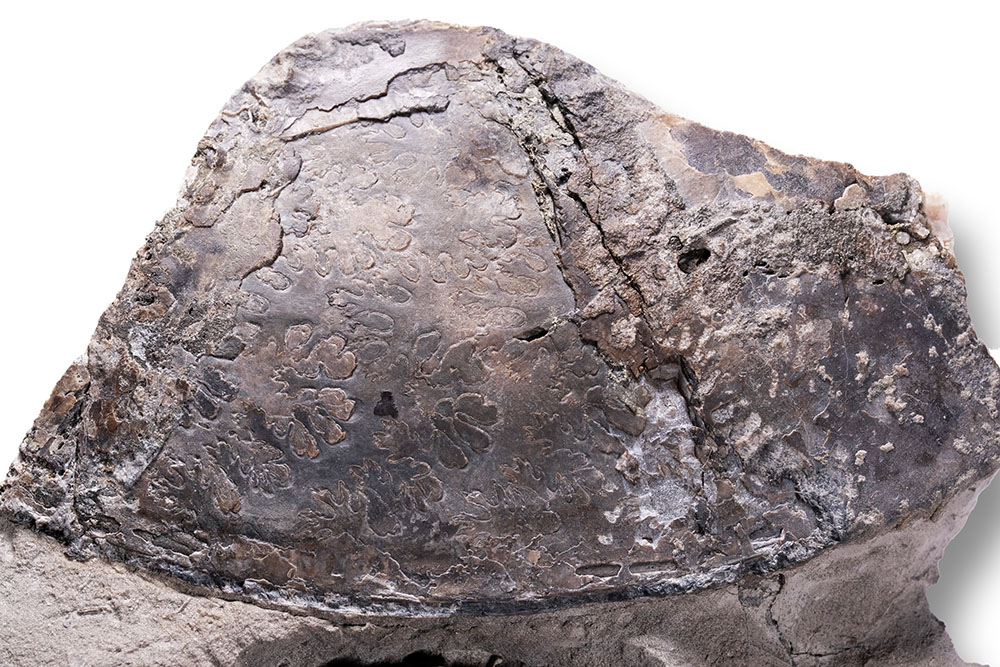

Pleuroceras hawskerense (YOUNG & BIRD)

Pleuroceras hawskerense, 107 mm

The Hawkser Pleuroceras – an iconic ammonite, evolved in Yorkshire – so truly

born and bred Yorkshire !

P. hawskerense has characteristic densely ribbed inner whorls, strong radial

ribs and a stong keel, rib density is always bigger than P. paucicostatum apart

in large body chambers of both species. P. hawskerense is best preserved in

bed 42 (shown here (link)) and 43 at the top of the hawskerense subzone,

the specimen pictured above is from bed 43.

These beds, especially bed 43, where exposed, have been more or less exploited

over the centuries, so that well-preserved new finds are rare.

Pleuroceras hawskerense (YOUNG & BIRD) transient elaboratum (SIMPSON)

Pleuroceras hawskerense transient elaboratum, 82 mm, Hawsker Bottoms

P. hawskerense transient elaboratum, in newer literature just P. elaboratum,

is a Pleuroceras population ancestral to P. hawskerense, specimen have the

same densely ribbed inner whorls, but higher rib density

(30 – 38 ribs instead of 25-30 in P. hawskerense) on whorls of more than

40 mm. Both the specimen in Whitby museum (WM:SIM302) displayed here :

and the specimen in my collection display a slightly sunken in keel on the

outermost whorl.

Pleuroceras hawskerense transient elaboratum, 130 mm, Hawsker Bottoms

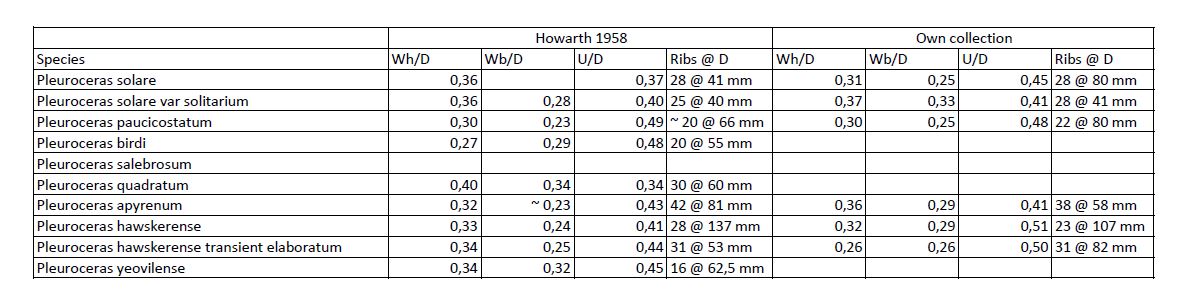

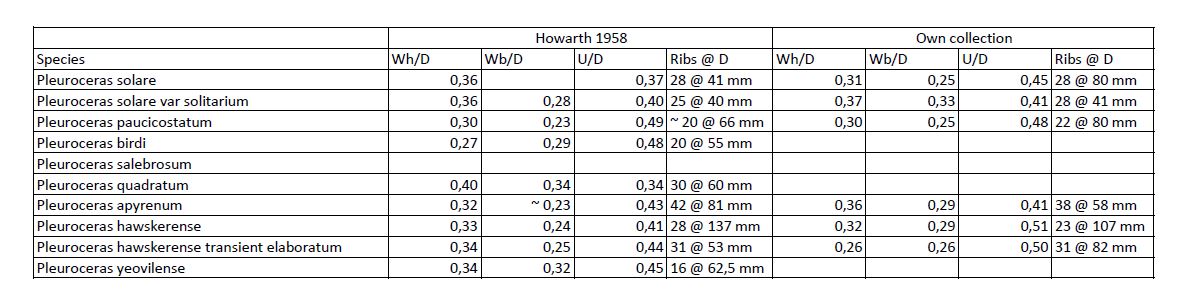

Summary of measurements

All measurements for the Pleuroceras species mentioned here, both for the specimen in Howarth´s monograph and the specimen in my collection

can be found here :

Measurements of Pleuroceras species

Rib density curves showing the complete variation of the species´rib density based

on ammonite diameter can be found in Howarth´s monograph.

So far this has been the blog post I invested the most work in – both in terms of

re-prepping specimen in my collection, and the amount of research needed until

I myself was happy with the result.

I´ve got a feeling that Pleuroceras is somewhat under-represented in Yorkshire

collections, may be because the ironstone nodules containing the ammonites

can be excruciatingly hard and tough – the name “ironstone” already says it,

I´ve many times given up on large nodules myself.

Therefore they rarely “pop open” with a perfectly preserved fossil, and

subsequently require significant work to prep the fossil – if at all possible,

when the inner whorls are preserved in a single “crystal” of solid calcite.

I hope I´ve shown that the result can be well worth the effort –

Pleuroceras is a stunning ammonite and some species are more or less

unique for Yorkshire.

AndyS

Addendum Feb. 26, 2017 :

Well, the Holderness coast has again delivered a surprise…

A friend who has recently visited the coast, sent me a picture today for identifiction.

The ammonite shown is a large, 140 mm diameter specimen and judging by the keel, is a

Pleuroceras – but it has massive thorns on the inner whorls !

Pleuroceras cf. yeovilense, 140 mm, Holderness Coast

The only Pleuroceras species that has thorns like this is Pleuroceras yeovilense, not usually known from this high up,

below the GeoEd cast of the holotype :

Cast of holotype of Pleuroceras yeovilense, 60 mm diameter

Congratulations to the finder and thanks for sending me the picture !

Literature

M.K. Howarth : The Ammonites of the Jurassic Family Amaltheidae in Britain, Palaeontographical Society London, 1958

K.N. Page : Castlechamber to Maw Wyke, North Yorkshire in : British Lower Jurassic Stratigraphy, JNCC Peterborough, 2004