Gagaticeras in my mind somehow is more of a coincidental find, casually picked up on the way somewhere else – which of course does not do this fine ammonite genus any justice.Around Robin Hoods Bay it has been reasonably common in the last couple of years (though I´ve noticed a drop in the last 2-3 years), I´ve mostly found them almost eroded free or in nodules that were thrown onto the beach during storms, the beds they occur in are very often sanded over – since most of the coast is a SSSI you´re not really supposed to do any large-scale digging in them anyway.

As you start collecting Gagaticeras ammonites, at first sight they mostly look the same (especially in the field), you put them in the drawer as “Gagaticeras gagateum”.

You collect some more, clean them up as good as you can (they´re not easy to prep well because of their delicate inner whorls), put them in the drawer.

After a while, when looking into the drawer at what you´ve accumulated over the years, you begin to wonder and see little differences, a more pronounced keel here, rursiradiate ribbing there, differences in rib density etc. A while ago after I acquired an air abrader, a re-preparation helped to work out some more details in the inner whorls.

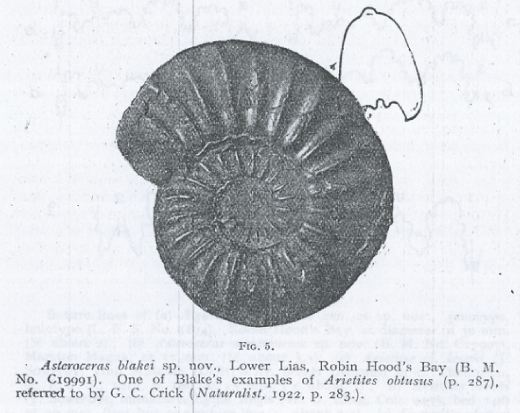

When starting to document the Gagaticeras species for the book, I was really surprised (and pleased of course 🙂 )to see that I do actually have the four species that HOWARTH mentions in his Robin Hoods Bay / Bairstow collection paper ! I must admit though that it did take me some time to find the most characteristic specimen

for each species, there seem to be many intermediates (like the one pictured above, which has a very high rib density but almost no keel and no rib angle at the venter), which all the authors that have recently written about them (HOWARTH 2002, SCHLEGELMILCH 1976, GETTY 1973,…) have taken as a sign that intra-species variation may make it appear that there are more species than there really are – but that´s always the problem when you do not have a large enough collection to do statistical tests.

Gagaticeras gagateum (YOUNG & BIRD, 1828)

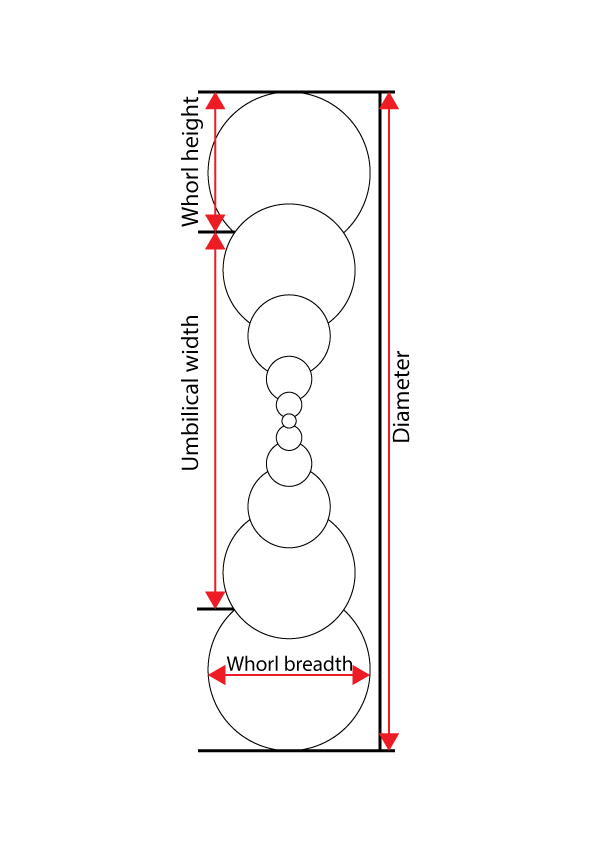

Whorl section is more compressed than on the other species, i.e. the whorl is thicker than high.

Gagaticeras neglectum (SIMPSON, 1855)

is less depressed, almost round. The expression of the keel seems to be very variable.

Gagaticeras finitimum (BLAKE, 1876)

Gagaticeras exortum (SIMPSON, 1855)

G. exortum is the easiest to identify : Ribs are quite rursiradiate (leaning backwards), there is just a hint of a keel.

If my collection were considered representative, it would be the rarest species of the four. Rib density on the figured specimen is

23 ribs / whorl at 30 mm diameter, another specimen I´ve seen has 26 ribs/whorl at 50 mm diameter.

In case you´re wondering what this all has to do with jet beads ?

Well, “gagateus” is the greek name for jet and the citation in this post´s title is from YOUNG & BIRD´s original 1828 description of “Ammonites gagateus”

and simply refers to similarity of the black whorls with jet beads…